New pictures of the Sun taken just 77 million km (48 million miles) from its surface are the closest ever acquired by cameras.

They come from the European Space Agency's Solar Orbiter (SolO) probe , which was launched earlier this year.

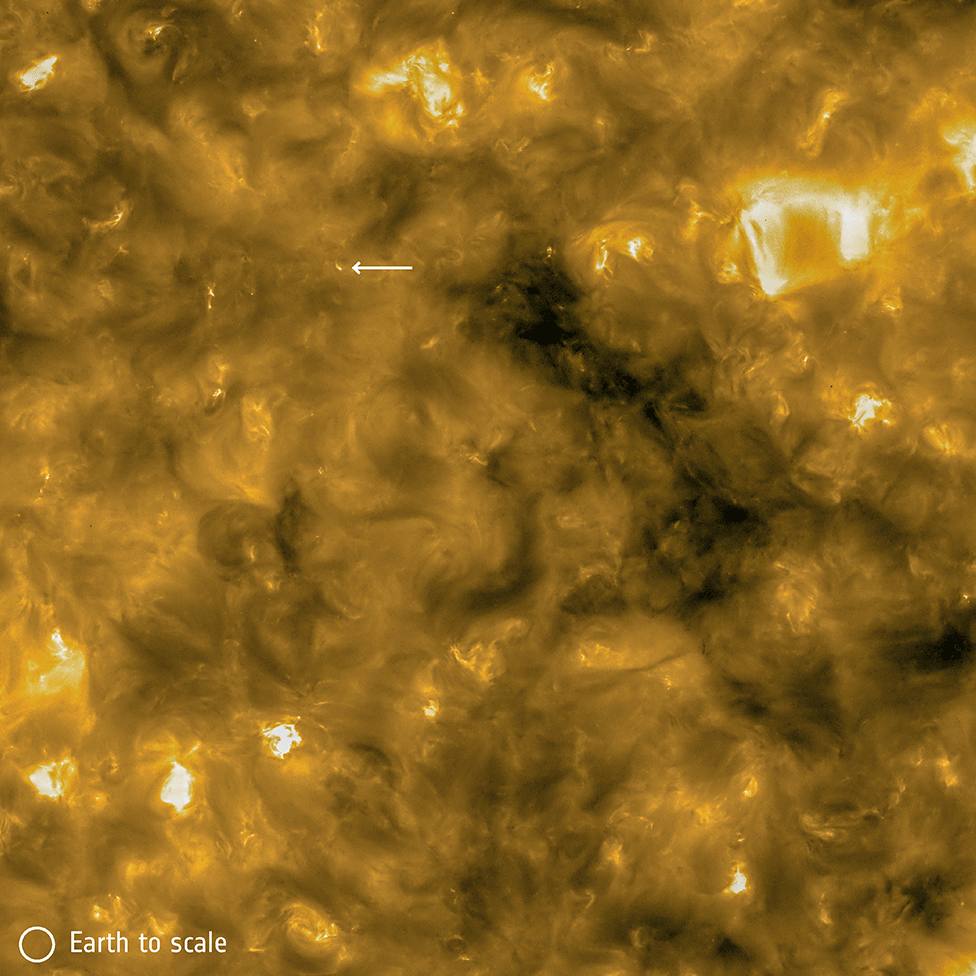

Among the UK-assembled craft's novel insights are views of mini-flares dubbed "camp fires".

These are millionths of the size of the Sun's giant flares that are routinely observed by Earth telescopes.

Whether these miniature versions are driven by the same mechanisms, though, is unclear. But these small flares could be involved in the mysterious heating process that makes the star's outer atmosphere, or corona, far hotter than its surface.

"The Sun has a relatively cool surface of about 5,500 degrees and is surrounded by a super-hot atmosphere of more than a million degrees," explained Esa project scientist Daniel Müller.

"There's a theory put forward by the great US physicist Eugene Parker, who conjectured that if you should have a vast number of tiny flares this might account for an omnipresent heating mechanism that could make the corona hot."

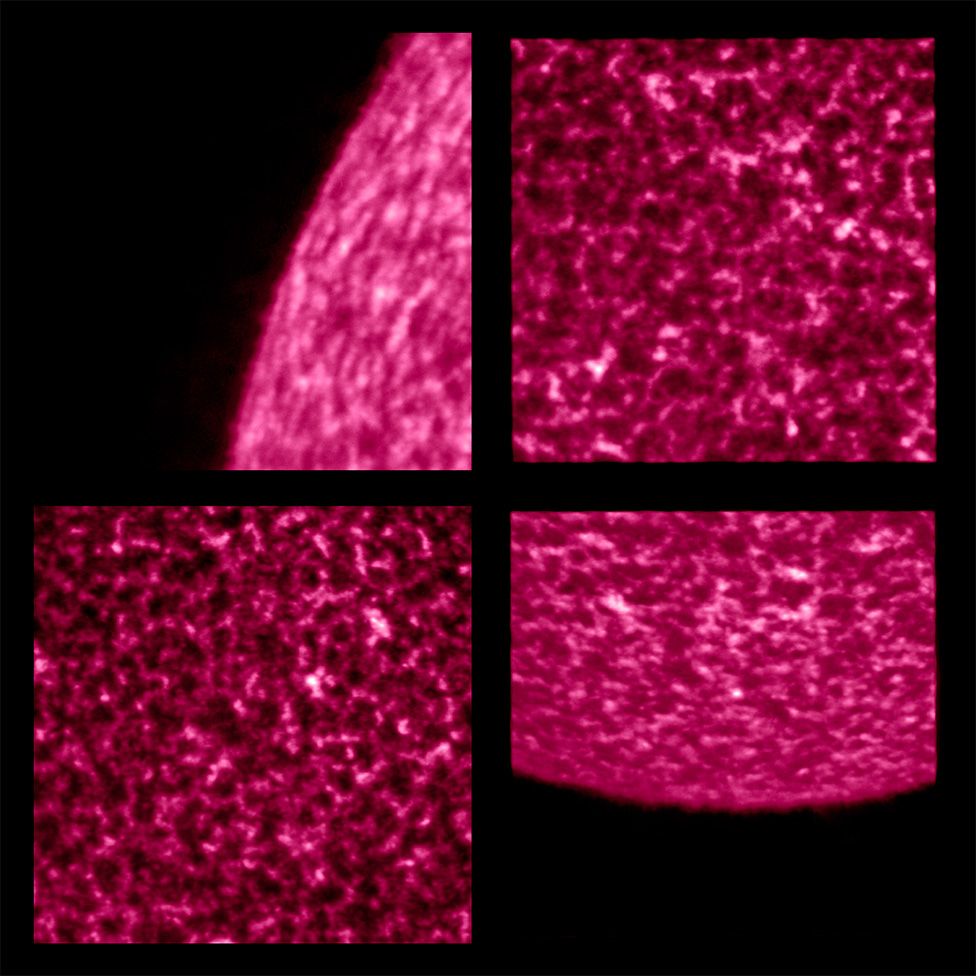

Whatever their role, the camp fires are certainly small - which may explain why they've been missed up to this point, says David Berghmans, from the Royal Observatory of Belgium and the principal investigator on the probe's Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI).

"The smallest ones are a couple of our pixels. A pixel corresponds to 400km - that's the spatial resolution. So they're about the size of some European countries," he told reporters. "There may be smaller ones."

- Solar Orbiter: Sun mission blasts off

- Sun's surface seen in remarkable new detail

- BepiColombo Mercury mission bids farewell to Earth

The European Space Agency (Esa) satellite was despatched on a rocket from Cape Canaveral in the US in February. Its mission is to reveal the secrets of our star's dynamic behaviour.

The Sun's emissions have profound impacts at Earth that go far beyond just providing light and warmth.

Often, they are disruptive; outbursts of charged particles with their entrained magnetic fields will trip electronics on satellites and degrade radio communications.

SolO could help scientists better predict this interference.

"The recent situation with coronavirus has proved how important it is to stay connected, and satellites are part of that connectivity," said Caroline Harper, the head of space science at the UK Space Agency. "So, it really is important that we learn more about the Sun so that we can predict its weather, its space weather, in the same ways we've learned how to do (with weather) here on Earth."

Solar Orbiter has been set on a series of loops around the Sun that will gradually take it closer still - ultimately to a separation of less than 43 million km.

That will put SolO inside the orbit of the planet Mercury.

The pictures showcased on Thursday come from the most recent near pass, known as perihelion . This occurred in mid-June, inside the orbit of Venus.

For comparison, Earth sits about 149 million km (93 million miles) on average from the Sun.

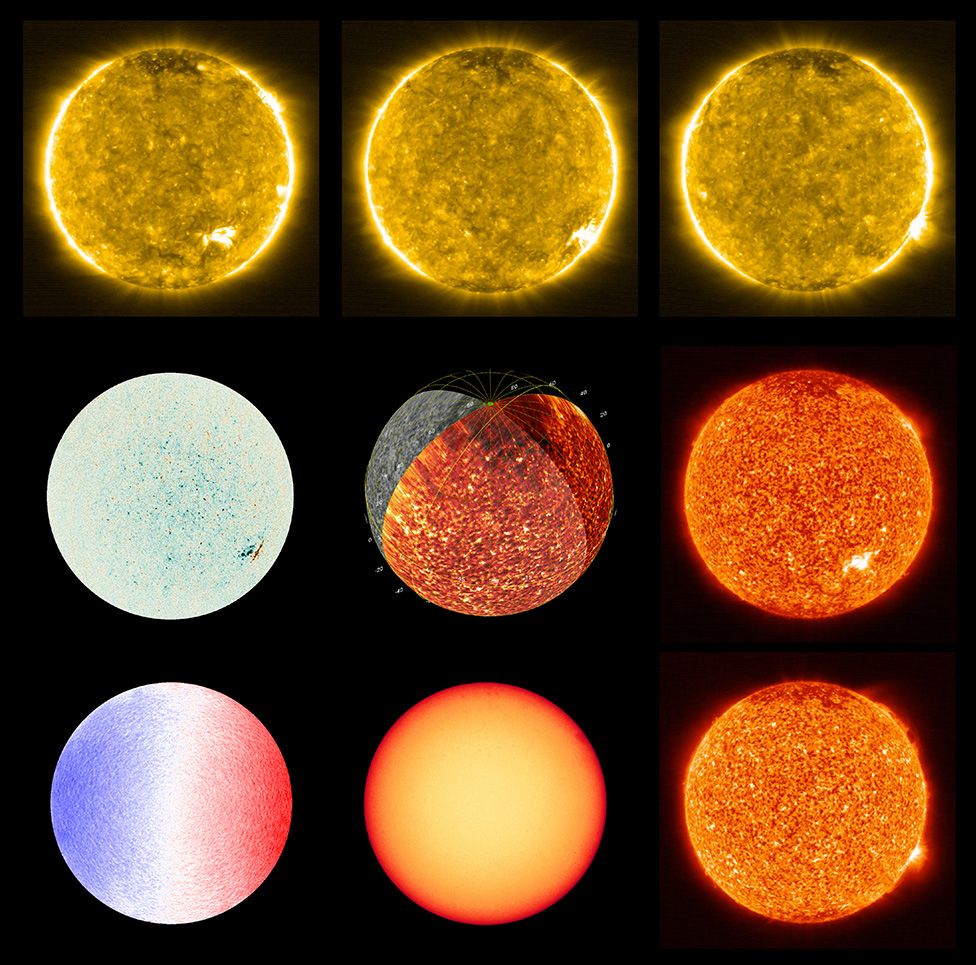

To be clear: while the new images have been taken from the closest ever vantage point, they are not the highest resolution ever acquired. The largest solar telescopes on Earth will always beat SolO on that measure.

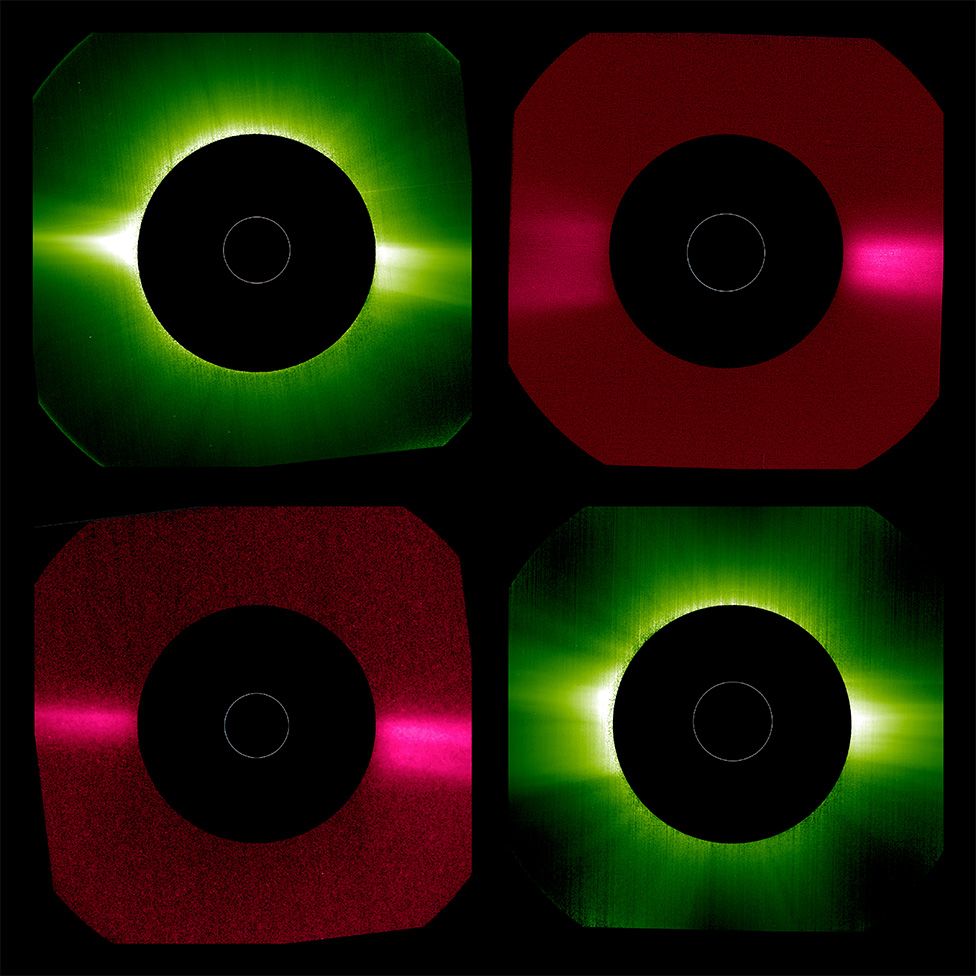

But the probe's holistic approach, using the combination of six remote sensing instruments and four in-situ instruments, puts it on a different level.

Esa's senior advisor for science & exploration, Mark McCaughrean, told BBC News: "Solar Orbiter isn't going closer to the Sun just to get higher-resolution images: it's going closer to get into a different, less turbulent part of the solar wind, studying the particles and magnetic field in situ at that closer distance, while simultaneously taking remote data on the surface of the Sun and immediately around it for context. No other mission or telescope can do that."

It will be a couple of years yet before Solar Orbiter makes the first of its very close encounters with the Sun (at a distance of 48 million km).

As the mission progresses, SolO will, with the gravitational assistance of Venus, also lift itself out of the plane of the planets so that it can more easily see the Sun's poles. "Terra incognita", as Sami Solanki, from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research and PI on Solo's Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager, likes to call these regions.

It's at the poles where we may finally learn the fundamentals of the Sun's magnetism.

"We know that the magnetic field is responsible for all the activity that the Sun produces, but we don't know how the magnetic field itself is produced," Solanki said.

"We think it's a dynamo that is doing that inside the Sun, similar to the dynamo inside the Earth. But we really don't know how it functions. But we do know that the poles play a key role."

Holly Gilbert, the Solar Orbiter project scientist at the US space agency, Esa's major partner on the mission, enthused about the science ahead.

"If we've already made some discoveries with just the 'first light' images, just imagine what we're going to find when we get closer to the Sun, and when we get out of the ecliptic. Very exciting."

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos